The joys of Dynamic Typing, Part Two - Mutables

In the first part of this text, we have seen that the defining characteristic of the Python is the dynamic typing; the possibility of creating variables without their declaration but rather with immediate assignation to the value; the easy-going reassignation to another object type and value. We have made the distinction between immutable and mutable variables and explained the variations when managing immutable variables.

Now it’s the time to refer to mutables and analyze their behavior to get a complete picture of assignment and reference model which is central in Python.

Mutable types

Mutable are considered following Python’s objects:

Lists. List is a mutable object type in Python which allow storing multiple objects in ordered manner. They are indexed - meaning the order of objects inside list matters and is being tracked internally. Lists are not fixed in size (like static arrays in C languages which Python doesn’t support); they are changeable; allow duplicate values and are mutable. This ensures an excellent flexibility of their use as the internal manipulations of its contents is automated (for instance, list automatically inserts or deletes particular containing object, rearranges the remaining indexes and the length attribute). Mutability means they can change content in place without creating another list, as we will see in examples.

Dictionaries. Dictionary is such data structure which allows storing values in key: value pairs. As in lists, order matters, they are changeable but they don’t allow duplicates – its keys are unique. Dictionaries are mutable as well and they are indexed as well, but through indexing one can access key or values, not both at once.

Sets. Sets can store multiple items in a single variable which is different from lists and dictionaries which store multiple objects; they are not ordered and not indexed; and are mutable.

Consider following statements:

1

2

3

List1=[1,2,3,4]

List2=List1

List1=”Hello World!”

This is an example of shared reference without changes inside a list. List1 and List2 link to the same object in the first two lines, then the List1 references another object (with another type) while List2’s reference remains unchanged. Note that we can access the lists’ elements through indexing so List1[0]=1, List[1]=2 and so on. Now we introduce the changes inside a list with shared reference:

1

2

3

List1=[1,2,3,4]

List2=List1

L1[0]=5

This code returns following:

1

2

List1=[5,2,3,4] # List1 changed in place, there was no new object, the old one is being modified

List2=[5,2,3,4] # List2 also changed since it references the same object

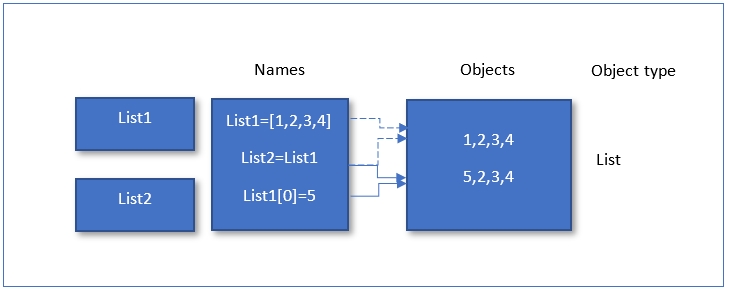

Figure 1: List’s mutability, i.e. changes in place result with no additional object being created

Figure 1: List’s mutability, i.e. changes in place result with no additional object being created

In the upper example we changed only object within the List1 which resulted in a change of the object’s value; therefore, no new object needs to be created. This is important to note because if there are multiple references to the list, they all will be changed as well, which may or may not be immediately understandable. So, when structuring the code, pay attention to the shared references as they will change upon the mutable object’s change.

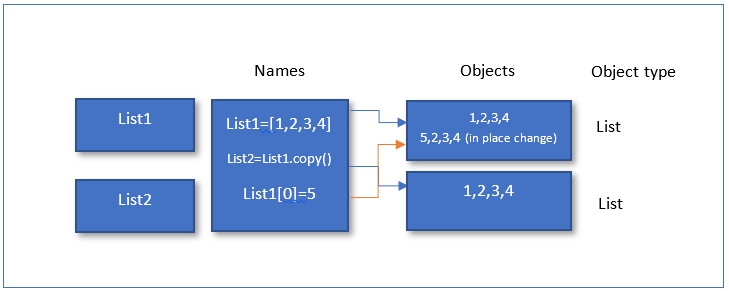

If we wanted different behavior, that is, only change directly affected variables, other with shared references to stay unchanged, we could use some workarounds. For instance, we may copy the value of the list when declaring another one:

1

2

3

4

List1=[1,2,3,4]

List2=List1.copy() # using the copy method creates another object

# List2=List1[:] using list slicing also creates another object while copying the values

List1[0]=5

After those changes, the lists’ printout looks like:

1

2

List1=[5,2,3,4] # took change in place, references the same object

List2=[1,2,3,4] # unchanged, references previously, through copying created object

Figure 2: List’s mutability on in-place change

Figure 2: List’s mutability on in-place change

Equality and identity checks in Python

As we create variables with references, some maybe shared between them, it is sometimes useful to check whether variables refer to the same object. Such a test could then be used when determining are two variables’ values and their objects are equal or not. The equality is the situation when variables’ values are the same; the identity comprises the fact if the variables point to the same object. Operator == tests for the equality while is operator tests for object identity. When comparing two variables, following is possible:

- two variables have the same values, or not,

- two variables have the same identities (point to the same object), or not,

- variables at the same time have same equality and identity, or not.

Examples:

1

2

3

A=[10, 20]

B=[10, 20]

A==B is true, A is B not true.

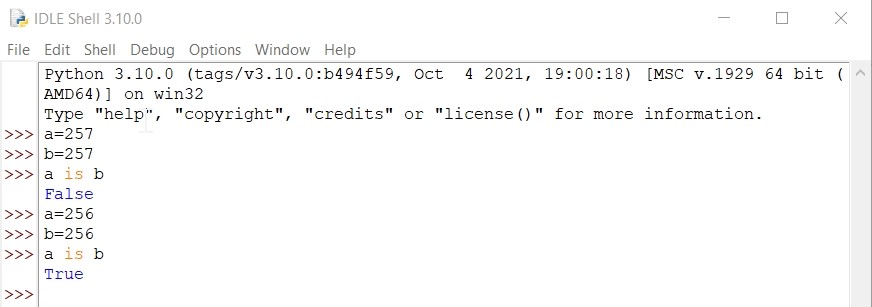

Using checks on integers, there is one thing worth mentioning regarding identity check. Because Python’s optimizations, if we compare integers’ identity in range -5 till 256, they will return the same object (although they shouldn’t), as such smaller integers are cached and reused:

Figure 3: Identity checks in Python’s default IDLE shell

Figure 3: Identity checks in Python’s default IDLE shell

However, this is not always the case as it seems that in the IDE like Visual Studio Code, interpreter still does some checks as it returns the same identity for the variables with the value of 257, so bear in mind those small grievances when testing your code:

Figure 4: Identity check printout in Visual Studio Code

Figure 4: Identity check printout in Visual Studio Code

Conclusion

In this text we’ve shown the behavior of mutables in the sense of their linkages to objects. Firstly, the mutables were defined and their types in Python explained. Secondly, we have explored their basic traits when reassigning their values and summarized the background changes in object’s references. It is important to test variables for equality and identity so through couple of simple examples we have highlighted some rules and exceptions to those rules, which may be of use when analyzing or debugging the code.