The joys of Dynamic Typing, Part One - Immutables

In traditional, statically-typed languages there is a data type classification which needs implicit declaration to every variable, function and OOP object. If the variable’s data type is for instance an integer, it needs to be marked as one prior to the value’s assignation. It is possible to declare a variable in one line, without assigning any value to it. It is however NOT possible to declare a variable and then to re-declare it implicitly as another type, or with another value. Static typing makes things more ordered, clear and defined for the compiler, which reduces the number of needed checks improving the bug-detection rate and compiling time. Downside is the syntactic complexity of a such written code which raises the costs of the development. On the other hand, dynamically-typed languages (of which two probably most used being currently Python and JavaScript) don’t declare variables, they assign them without mentioning of any data type whatsoever. If we instead of

1

int x=5;

simply state

1

x=5

one may ask, how does the Python know that variable x is intended to be used as integer?

Names, references, objects

In Python, variable is created when we assign a value to it. There is no declaration of variables prior to the assigning value (btw. proper “pythonic” designation is name rather than variable, but we’ll stick to the latter for the sake of clarity, especially in comparison with another languages). A variable only has its name, the type of it doesn’t exist as the variables are generic in nature and only refer to the particular object created in memory for designated amount of time. This may be baffling to C/C++/Java/C# developers. When a variable is being created with an assignation to some value, the Python immediately creates an object and references a variable to that object. Unassigned variables can’t exist and an attempt to do so leads to an error. More specifically, the statement:

1

x=5

does the following in Python:

- interpreter checks the value, conduct some tests and make a conclusion about the type,

- object with proper type is created to represent the value 5,

- variable x is created, more specifically name,

- reference is created to link variable x with its object.

Variables are separated from objects and stored in different parts of the memory while being linked together. Simple variables exclusively link to objects, while more complex objects (for instance lists and dictionaries) link to the objects they contain. References or links are strictly enforced; therefore, Python really uses only names for variables and for that matter a name can’t have a type, but object can. That is the answer to the question how Python knows the type of the variable: it doesn’t, but it does know the type of the object that variable is being referenced to. Objects are spaces in memory but more than that - they have two header fields:

- type designator, which actually identifies the type of the object, and

- reference counter, which holds a number of times the object is being referenced.

In Python, references are pointers which point to some address in memory (similar to C pointers), but given the important fact that the Python has garbage collector, since the variables are being automatically referenced, they are automatically unreferenced on certain conditions as well – hence, there is no way to use them in such a manner - it is pointless.

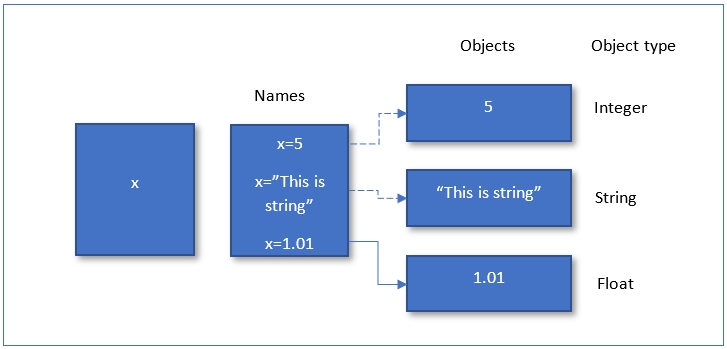

Because of such structure, it is possible to change the value type of the variable:

1

2

3

x=5

x="This is string"

x=1.01

Figure 1: The variable x can change values and types because in the background it only refers to various objects which are created and destroyed

Figure 1: The variable x can change values and types because in the background it only refers to various objects which are created and destroyed

As described, the variable x doesn’t really change its type but name x changes it’s referenced object which changes the type. Variable, i.e., name does not have the type, it is only an internal notion, but objects through type designator recognize the particular type. What happens when we change the variable’s assignation? Whenever a name being assigned to new object, if the object referenced prior to that loses all references, it is being automatically reclaimed – beforementioned garbage collector kicks in.

1

2

3

x=5

x="This is string" # if number of references to it equals zero, object with value 5 is being reclaimed

x=1.01 # “This is string" object is reclaimed

Immutability explained

This discussion leads us to the notion of immutability. Broadly speaking, in programming jargon, a variable which value can’t be changed is considered immutable. In Python, immutability is achieved at object level and immutable are core types of objects (partially similar to primitives in C languages):

- integers,

- strings,

- tuples.

They can’t be changed in place; therefore, on change of assignation we need a new object to represent the new value and/or data type. Mutable are considered following Python’s objects:

- lists,

- dictionaries,

- sets,

- most custom created OOP objects.

Those can be changed in place as we can see in the part 2 of this article.

Multiple (shared) references

Until now, we have been assigning values with some values, which creates objects in the background. There is another possibility - assigning variable to another variable:

1

2

x=5

y=x

In this case, there is only one referenced object, which has the value 5. When we say y=x, there is no new object, but what happens is creation of another reference to the existing object. Object with value 5 is shared among two variables, but those variables do not have any connection whatsoever (in stark contrast to C languages); via references they point to the very same object. Let’s broaden this contemplation a bit more, by saying:

1

2

3

x=5

y=x

x="Hello World!"

Figure 2: If we assign one variable for another, those variables will not be linked but point to the same object. If we further assign a new value to the first variable, it will point to new object while second one will remain pointing to the previously referenced one.

Figure 2: If we assign one variable for another, those variables will not be linked but point to the same object. If we further assign a new value to the first variable, it will point to new object while second one will remain pointing to the previously referenced one.

Here the variable x changes reference, so when the last line is typed, Python creates new object with the name “Hello World!” and new reference to it, while previous one is being dereferenced and removed from the memory (if there are no other references linking to it). Note here that the value of the y remains the same: object with the value 5 is being still referenced by y. The same holds true if we don’t change type, for instance:

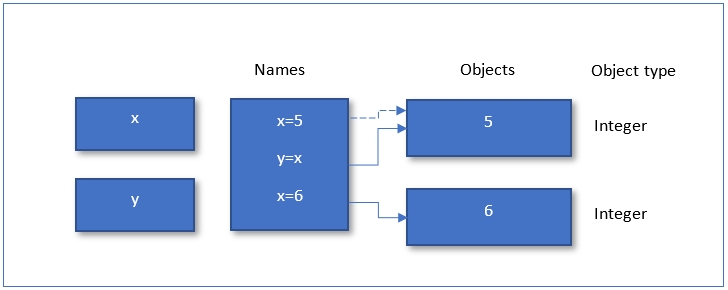

1

2

3

x=5

y=x

x=6

Figure 3: Same as Figure 2, but without change of the object’s type

Figure 3: Same as Figure 2, but without change of the object’s type

The object we initially created holds the value represented with integer 5, when we created new variable, we added another reference to the same object, and finally, as we assigned new value to the variable x, new object is created while first one remains referenced to variable y. Once again, variables in Python only point to objects and do not represent actual memory spaces, therefore it is impossible for immutable objects to change values.

Conclusion

Dynamic typing is such an important characteristic of Python. It enables the great flexibility and freedom of expression, but it does have its drawbacks as the interpreter must constantly perform numerous checks on runtime, reducing the speed of execution. This article has shown the main behavioral traits of dynamic-typed code in terms of using immutable objects and the corresponding logic behind it. I would argue that while it certainly may be cumbersome to switch from static to dynamic-typed code, but going from dynamic to static scheme is much more demanding, requiring more precision and attention to details.