Behind Python's lines

The final product of the user’s code in Python is .py file. On its execution, the source file is passed to a Python as an argument, compiled to the intermediary byte-code and then interpreted in the Python Virtual Machine. A lot of happenings, most of which is hidden to the user. Why care, if the code runs appropriately? There are a couple of reasons:

Getting the fine-grains will hone your conceptualization and coding skills. As you go deeper to the more fundamental programming concepts, you will learn a lot; open your mind to the new concepts and broaden your views.

Start thinking about the code’s complexity, efficiency and optimization, even if it may sound futile as Python’s engine is already many times optimized. Those are not only theoretical aspects, but can be practical, depending on the usage. For those who will care about the program speed, there could be possibilities to accelerate your program by an order of magnitude – by telling the Python which exactly optimization to apply (and maybe, which one to omit).

Academic, professional or personal curiosity to study how things are made.

Maybe you want to write your own programming language.

Python blends

As it turns out, Python has multiple implementations written in different languages. When we say Python, which actually is a specification, we usually think on its standard implementation called CPython and written in C and Python. It serves multiple roles: it is an interpreter, a compiler, a standard library, a parser and much more. There are many other variants, like Jython (Python implemented in Java), IronPython (.NET implementation), PyPy (fast-running Python, interpreted and compiled to optimized machine code), Cython (static-typing support, compiling to C code, really fast), Stackless (implemented in PyPy) and so on. In this text we will be considering CPython.

Intermediary code

In contrast to C/C++ which compile directly to machine code on a given platform and execute directly on CPU using its native instructions (therefore being fast as it gets, actually only thing that could be faster would be executing assembly instructions), Python compiles the source code into bytecode, which is assembly-alike, intermediary code with its syntax and semantics which is then interpreted in Python’s virtual machine (not on the CPU). So, Python adds one layer of abstraction between hardware and operating system, executing its bytecode internally on virtual software, achieving universal portability, but loosing speed: while C/C++ code must be compiled prior to run on any particular platform, Python (just like Java) runs platform-independent because it executes virtually. So basically, bytecode is a language hidden behind the Python’s code and developers usually do not bother with it nor the majority of users probably are aware that it exists. That is one of the reasons why Python is a high-level programming language: through automatization and optimization, it hides many steps from the developer, achieving clear, readable, human-language alike syntax which comes at the price of creating overhead and increasing complexity on its executing side which affects performance.

Analyzing bytecode

There is a way to disassemble bytecode by using the dis module. https://docs.python.org/3/library/dis.html The dis module disassembles Python source code into internal, individual instructions which are executed by the interpreter. So, for this basic code:

1

2

def Func(a):

print(a)

applying

1

dis.dis(Func)

we get following output:

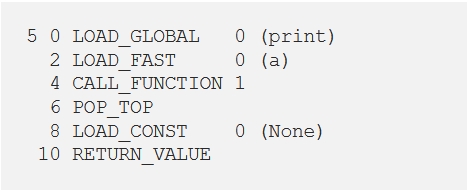

Figure 1: Disassembling function Func()

Figure 1: Disassembling function Func()

This is an example of disassembling one function, but it may be a complete .py file as well. This outputted code is the way the Python interpreter sees our code: it consists of internal instructions and their names and addresses which correspond to the original source code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

import timeit

import dis

def fast_compute():

return 100*12*30*24*60*60

def slow_compute():

seconds_hourly=60*60

hours_monthly=30*24

months_yearly=12

years_century=100

return seconds_hourly*hours_monthly*months_yearly*years_century

dis.dis(slow_compute)

dis.dis(fast_compute)

print(timeit.timeit(slow_compute))

print(timeit.timeit(fast_compute))

Output:

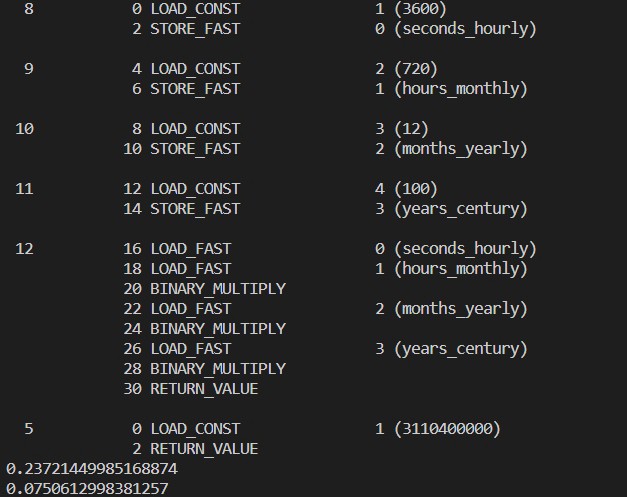

Figure 2: Disassembling functions slow_compute() and fast_compute()

Figure 2: Disassembling functions slow_compute() and fast_compute()

We defined two functions which compute number of seconds in a year, one function uses variables to store the corresponding time frames, while another computes it directly in the function’s return statement. We then tested the execution time of those functions and provided their corresponding disassembly code. The time of execution for the slow_compute function was 0,23 seconds comparing to the fast_compute one of 0,07 seconds (~3x slower). The slow_compute function has 16 lines of code while fast_compute has only two! The reason for this is that the interpreter knows that product of multiplication does not need to be reevaluated and computed again, while in the slow_function we used a number of variables, each of which needs to be checked in terms of their content as Python is dynamically-typed language which takes additional time when executed in virtual machine. By knowing this we could optimize our code for a three times faster execution, which is an outstanding gain.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

import timeit

import dis

def fast_loop():

for i in range(100):

pass

def slow_loop():

i=0

while i<100:

i+=1

dis.dis(slow_loop)

print()

dis.dis(fast_loop)

print(timeit.timeit('slow_loop()', setup='from __main__ import slow_loop'))

print(timeit.timeit('fast_loop()', setup='from __main__ import fast_loop'))

Output:

Figure 3: Disassembling functions slow_loop() and fast_loop()

Figure 3: Disassembling functions slow_loop() and fast_loop()

It is noticeable that the for loop is much quicker and with less internal instructions: 1.36 against 4.79 seconds is a huge time difference. This is due to the fact that it is internally optimized to run much faster C code, on the other hand while loop repeats much of its instructions and is interpreted which affects performance. Down to the bytes We could go even deeper and disassemble the already disassembled intermediary code into the stream of bytecode by using the function.code. For instance:

1

2

3

def calculate():

return 50**45+18*2/3

print(calculate.__code__.co_code)

returns

1

b'd\x01d\x02\x13\x00d\x03\x17\x00S\x00'

What those bytes stand for? They are low-level specifications of the intermediate instructions we already seen, which are then being fed into the virtual machine and actually executed. So, your code is dismantled into byte representations and then run on virtual machine which does another level of abstraction by separating the bytecode from actual, native code which all CPUs need to be able to produce a valid output. Long way down from writing “Hello world”!

Conclusion

This article gives a broad overview on Python’s interpreter internal dealings. It shows that Python, being a high-level language, consists of multiple layers of abstraction which hide many assembly details from the end user, providing an ease of use, readability, portability, automatic optimization and more. The only drawback is running time which, depending on one’s particular usage, may or may not be the issue.